I wasn’t planning to stop. I was halfway through a long ride, the kind you take when you’re trying to outrun something in your own head. But then I spotted a kid on the sidewalk, shooting a beat-up basketball into a rusted trash can and crying like his whole world had collapsed. That’s what made me pull my Harley over.

He couldn’t have been more than seven. Skinny kid drowning in a Lakers jersey big enough to use as a bedsheet. No shoes—just socks on cold pavement. And he kept throwing that ball at the trash can with this desperate determination that didn’t belong on a child’s face.

“Hey, buddy,” I called out. “You alright?”

He turned and looked at me. I’m not exactly the type kids run toward. Six-foot-two, two-forty, fully inked, leather vest with a half dozen patches, gray beard, the whole biker stereotype. Most kids would bolt. This one walked right up to me like I was the first safe thing he’d seen in weeks.

“My daddy said he’d buy me a basketball hoop if I made a hundred shots in a row,” he said, wiping tears on his sleeve. “I finally did it yesterday.”

“That’s impressive,” I told him. “So why the tears?”

His chin shook. “Because Daddy’s not coming back. Mama said he went to heaven last week. Car accident. He never got to watch me make the hundred shots.”

The air left my lungs. My hands shook. I’d lost people before, but seeing a child carry grief that heavy—it hits like a punch.

“I keep practicing anyway,” he said. “Maybe Daddy can see me from heaven. Maybe he’ll still be proud of me.”

I had to look away so the kid wouldn’t see a grown man break down. My voice came out rough. “What’s your name, son?”

“Marcus. Marcus Williams.”

“Marcus, I’m Robert. I’m real sorry about your dad.”

He glanced at my bike. “My daddy liked motorcycles too. Said he was gonna teach me to ride someday.”

I crouched down. “Where’s your mama, Marcus?”

“Inside. She’s been real sad. She doesn’t talk much anymore.”

“Mind if I check on her?”

He hesitated, studying me like someone twice his age. Then he nodded. “Okay. But she won’t answer. She doesn’t answer for anyone.”

We walked to the small house—paint peeling, porch sagging, the kind of place grief sinks its claws into. I knocked. Nothing. Knocked again.

“I told you,” Marcus whispered.

“It’s alright,” I said. “We’ll wait.”

We sat together on the porch, me and this little kid with socks soaked from the pavement. Twenty minutes later, the door cracked open and a woman appeared. She looked young but worn down, eyes hollowed from crying, voice dull as sandpaper.

“Who are you?”

“Ma’am, my name is Robert Crawford. I stopped because I saw your boy practicing. He told me about his father.”

Her face broke instantly, like it was barely holding together. She gripped the doorframe so she wouldn’t fall. “I can’t… I can’t buy him a hoop. I can barely keep the lights on. Jerome was the one who worked. I’m looking but nobody’s hiring, and the funeral costs—”

Her words collapsed into sobs. The kind that don’t stop once they start. The kind that come from somewhere deep.

I reached into my vest and pulled out everything in my wallet. $347. My gas and food money for the week. I handed it to her.

“No,” she said, stepping back. “I can’t take charity.”

“This isn’t charity,” I told her. “This is one parent helping another. I lost my son years ago. I know this pain. Please take it. Feed your boy. Pay something off. Just breathe for a day.”

She broke again. Marcus hugged her waist. “It’s okay, Mama. The motorcycle man is nice.”

I nodded toward Marcus. “He told me about his hundred shots. Told me about the promise. I can’t bring his father back, ma’am. But I can keep that promise.”

She froze. “You’re not serious.”

“I’ll be back in an hour.”

I rode straight to a sporting goods store. Walked in still covered in road dust and leather. Found the hoops. Picked a solid one—not the cheap junk, not the overpriced nonsense, just something that would stand tall for years.

“Can you deliver this today?” I asked the clerk.

“We usually don’t—”

I slid my credit card across the counter. “I’ll pay whatever it takes.”

He looked at the address I’d written on the receipt, then back at me. “Sir… I’ll take it myself after my shift.”

“Appreciate it,” I said.

When I got back, Marcus was already waiting by the curb. “You came back!”

“I told you I would.”

He shrugged. “Most people say they’ll come back. They don’t.”

That one hurt. Kids shouldn’t know that kind of truth.

His mom stepped out with two glasses of water. She looked tired, but she’d put herself together. “Mr. Crawford… you don’t know what today means to us.”

“Just take care of yourself,” I told her. “That boy needs his mother standing.”

An hour later, a pickup rolled into the driveway with the basketball hoop in the back. Marcus’s jaw dropped. “Is… is that for me?”

“You earned it,” I said. “A hundred shots is no joke.”

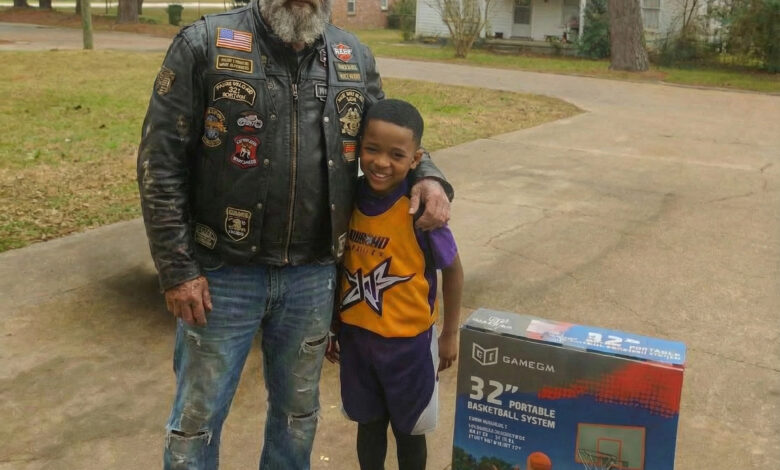

He ran at me and hugged me so hard my ribs might’ve cracked. “Thank you, Mr. Robert!”

His mom hugged me too, crying into my vest. “I don’t have words.”

“Then don’t say anything. Just let me help.”

Marcus and I set the hoop up together. I taught him how to use the wrench, how to line things up, how to check his work. He asked about my patches, about my club, about the rides we do for kids and families.

“Are bikers good guys?” he asked.

“Most of the ones I know are,” I said. “We just look scary.”

When the hoop was ready, Marcus grabbed his beat-up basketball and took the first shot. It swished clean through the net. He screamed with joy and looked straight at the sky like he was showing his father.

“He’s good,” I said quietly.

His mother nodded. “Jerome practiced with him every night. Said Marcus was going to get a scholarship one day.”

“Well,” I said, “he’s gonna need someone to practice with. If you’re alright with it… I’d like to come by sometimes. Shoot hoops. Be there for him.”

“You’d do that? For a child you just met?”

“I can’t get my own boy back,” I said. “But I can be here for yours.”

She took a long breath. “Jerome would’ve liked you.”

Eight months later, I’m there every Saturday. Sometimes more. I help Marcus with homework. We grill burgers. We shoot until dark. His mom found a job and started getting her life back piece by piece.

Last weekend, he turned to me after sinking a tricky shot and said, “Mr. Robert, can I call you Grandpa?”

I couldn’t speak. I just nodded and held him.

“I love you, Grandpa,” he whispered. “Thank you for coming back.”

I held that kid and let the tears fall. “I’ll always come back, Marcus. Always.”

A trash can and a worn-out basketball. That’s all he had. And somehow, it was enough to lead me straight to the grandson I didn’t know my heart was waiting for.